SPINAL DECOMPRESSION, PART 2

Nov 01, 2021My friend and colleague, Dr. Jerome Fryer, in British Columbia has conducted a pilot study on loading and unloading the spine using a seated spinal decompression technique. He has graciously given me permission to reprint (and reword) one of his recent blog articles, relating to his decompression technique. This article is all about

- How and why decompression works

- Q&A about decompression

- Other decompression techniques [provided by me]

DR. FRYER EXPLAINS SPINAL COMPRESSION...

Too much compression on the spine can be damaging when the forces are beyond what the discs [and vertebral end plates] can withstand.

Spinal compression is a natural result of gravity, aging and sport.

Logically then, it’s reasonable to expect that decompressing or uncompressing your spine would be a solid approach to the issue of constant compression.

In order to consider decompression exercises though, it’s helpful to better understand how the spine works. Although we often think about bones being in and out of place, let’s consider instead that the spine is a very cool hydrostatic system.

Let's start at the basics: Your spine is made up of bones and soft tissue.

Your vertebrae contribute to two-thirds of the total height of your spine, while your discs make up the other one-third. Your boney vertebrae are full of blood and pressure, but your discs not so much!

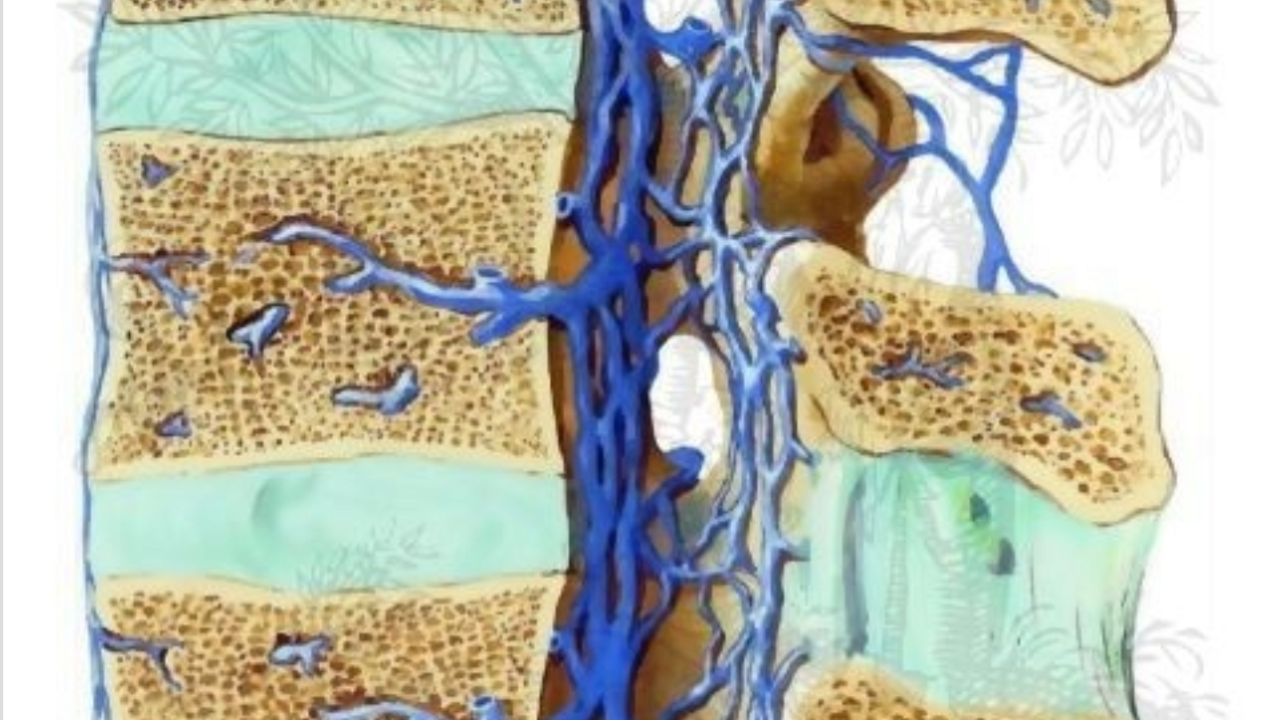

Your vertebrae have arteries pushing blood into them and act like charged canisters of blood with strainers at each end which select parts of the blood through-passage.

Now comes the good stuff:

HYDROSTATICS

If there is no blood in the disc, then you may be asking, how does it survive?

All cells in the human body need oxygen and glucose to live. The key lies in the fluid which flows in and out through an intricate network of pipes.

The fluid in your discs comes from your blood which is transferred (and strained) via your movement.

The centermost part of the disc, called the nucleus pulposus, loves water and it has negatively charged proteins in it called proteoglycans which magnetically bond to water. Pretty cool, huh?

The more of this proteoglycan protein that is around, the better the disc can absorb fluid, like a sponge and it’s this sponginess that both absorbs force and helps to maintain enough space between your vertebral bodies.

When too much compression is placed on these discs, hydration is squeezed out and you are left with a drier sponge which can’t resist compression, often resulting in what the medical community has unfortunately termed Degenerative Disc Disease.

When your discs lose hydration, they flatten, allowing the vertebral bones to get too close to one another. Because so many nerves run through these areas, less space may result in nerve compression and…nerve pain.

If you rest too much though, anti compression occurs, and due to the lack of hydrostatic mechanics happening when you rest too much, your discs may swell up, leaving less space and putting even more pressure on your nerves.

It’s a delicate balance.

SPINE HYDROSTATICS

Back to hydrostatics, because this is where it gets interesting!

All cells in the body need oxygen and nutrients to survive but they also need to get rid of the byproducts.

Your arteries carry food and water in and while your veins get rid of the liquid junky by-products. So, hydrostatics refers to how your discs naturally pressurize to facilitate this tidal flow of nutrients coming in and by-products flushing out.

Herein lies the difference between traction and what I perform called anti compression or unloading spinal decompression (USD).

DYNAMIC SPINAL DECOMPRESSION

My pilot study was published in The Spine Journal. I had a clinical hunch that discs respond better to dynamic spinal decompression. When I looked at the MRI images after subjects performed Chair Care (an exercise I tested, which is now also referred to as Dynamic Seated Exercise or Seated Decompression), the discs plumped up in height.

But why? And how?

BATSON'S BIDIRECTIONAL VEINS

Did you know that most of the veins in your body only have one way valves?

Your spine, however, features a unique cerebral venous system called the Batson’s Venous Plexus (a.k.a. Batson’s Veins) that allows blood to move both ways.

Batson’s veins are the only veins in your body with two-way valves.

This bidirectional flow of Batson’s veins PLUS the loading/unloading of your intervertebral discs [which happens from going in and out of decompression exercises] are both critical for moving blood and pressurizing your discs.

👆🏼THIS is how you can affect fluid flow exchange in and out of your discs!

COMMON QUESTIONS

As a chiropractor, I get many questions regarding the concept of decompression. Some of them are:

-

Are those inversion tables any help?

-

How about gravity boots?

-

Does hanging from monkey bars help?

-

Is a hot tub good for my back?

-

Why does traction not help my back but your treatment does?

Are those inversion tables any help?

Hanging upside down may be fine to stretch out the soft tissues but it does not provide the fluid flow effectively to ( and from ) the discs. After about 5 seconds of hanging upside down the fluid slows down considerably and to create fluid flow, you’d have to stand up again to reload the spine.

How about gravity boots?

This is basically the same answer as above but with the added unnatural forces to the ankles.

Does hanging from monkey bars help?

It can if you have good shoulders but I would recommend getting off the monkey bars after about 3-5 seconds and then repeat.

Is a hot tub good for my back?

This environment is good to unload discs and relax muscles but you have to be careful that you are not heating up structures that are inflamed as this can exacerbate symptoms.

Why does traction not help my back but your treatment does?

Often I will have patients wonder why USD works well with spinal conditions. I believe it is possibly the pulse of load to unload that generates the best outcome.

Thanks, Jerome!

DINNEEN’S COMMENTARY

I'm a huge fan of gentle dynamic decompression exercises because they've helped me and many of my clients tremendously.

Now that we know a bit more about this hydrostatic mechanism we can conclude the following:

- Movement is necessary to move inflammatory proteins out of your spine and to flush healing hydration into your discs.

- The key is alternating decompression + load + decompression several times to optimize the fluid flow in and out of your discs

- Not moving exacerbates inflammation and impedes the hydrostatic mechanisms that are necessary for healing

MORE WAYS TO DECOMPRESS

There are many ways to dynamically decompress your spine.

I've posted several other ways to decompress on my Instagram feed, so take a look and make sure to follow me if you're not already.

These exercises may offer some relief for you if you have stenosis, dessicated (degenerative) discs or impinged nerves.

If you have been diagnosed with unstable spondylolisthesis, this may not be for you.

Note: This article is for informational purposes and is not meant as medical advice. Check in with your attending doctors and physical therapists to see if this would be appropriate for you.

Go here to read SPINAL DECOMPRESSION, PART 1